BACKGROUND

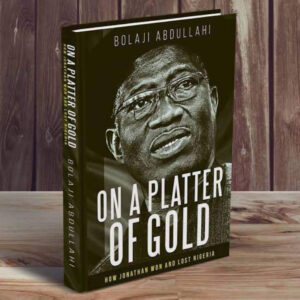

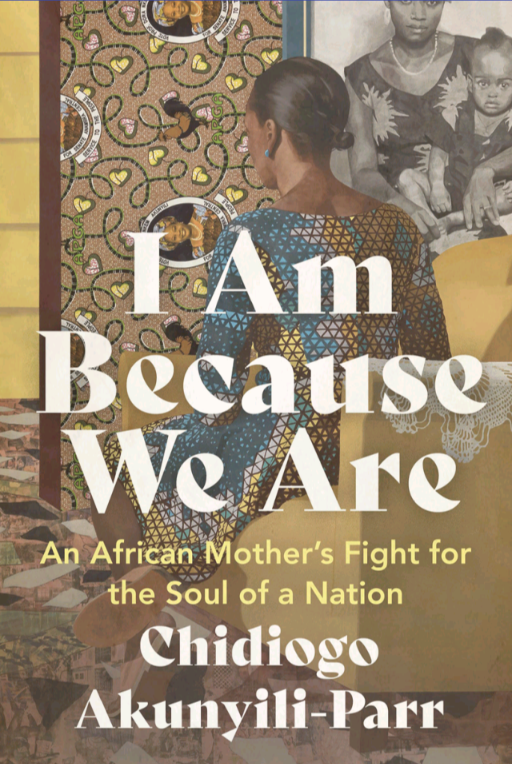

Basic literary taxonomy provides that a biography is a published story of a person’s life, while an autobiography is “A self-written biography; the story of one’s own life” (Wiktionary mobile version). I Am Because We Are: The Story of Dora Akunyili is a biographical work. Written in the first person (the persona), it is easy to presume that it is an autobiography, written by Dora Akunyili. That is not the case. It is actually written by Chidiogo Akunyili-Parr, Dora’s daughter, adopting the persona of her mother, the subject of the book. On page 366 of the book, we have the author’s testimony that she received an inspiration to write the book, with an unmistakable emphasis to “Write in my voice”, which is subsequently elaborated with “Speak with all voices.”

Perhaps in obedience to that instruction, the author feeds us with a rich diet of intimate details and transparent candour throughout the narrative. However, she does not tell us whether the details were secured from a diary kept by Dora Akunyili or a draft she wrote before her passing on. We are made to wonder if some of the details were made up in exercise of poetic license. In any case, my first impression of I Am Because We Are: The Story of Dora Akunyili is that it is a mine that would interest scholars interested in examining and analysing the sources of literary creations.

I Am Because We Are: The Story of Dora Akunyili is a book which states its purpose at the end – the “Epilogue: Chidiogo and Dora” (pp. 369-372) and “Afterword” (373-378). The reader is persuaded to accept that the purpose of The Story of Dora Akunyili is to guide us, especially Nigerians to appreciate that “A society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in” (p.378). This proverb is captured by the concept of “Ubuntu”, “…an interconnected web of humanity that binds us all” (p.370). Ubuntu is also a problem solving, conflict management principle that helps humanity to seek a solution outside the selfish antagonism of thesis and antithesis (Stephen R. Covey, The 3rd Alternative: Solving Life’s Most Difficult Problems, 2011, pp. 34-35). It is also consistent with the social philosophy of the Kalabari captured in the expression “Amatemeso”, the national creative essence and collective unconscious of the nation that makes the individual aware that his destiny is bound up in that of the collective. Thus, the Kalabari say, “if my nation smells pleasantly, it will rub off on me too”.

STRUCTURE AND CONTENT

I Am Because We Are: The Story of Dora Akunyili is divided into six broad parts, a “Prologue” (which includes the family tree of Dora Akunyili), an “Epilogue”, and an “Afterword”. It also has an index of mainly names. The first part is entitled “Dora” 1954-1972. Hosting the first 15 chapters of the book, it introduces us to Dora – her birth, childhood, primary and secondary education, which is punctuated by the Nigerian civil war.

Each chapter is headed by a proverb, pithy saying or quote. For instance, chapter 1 is entitled “A name is both a prayer and a story”. It is about the prophetic import of the full maiden name of our subject: Dorothy Nkemdilim Edemobi, which roughly translated means “Gift of God whose destiny will be fulfilled so that I may rest my soul”. We are given an account of how her parents met, and her early non-formal education (some may say, indoctrination) through the stories her father told her. In the process, Dora learns to appreciate certain philosophical ideals like “A name in Igboland is worth more than gold” (p.7); “the transient nature of things” (p.3); and “Success is measured over the course of one’s lifetime and marked by the lives touched” (p.9). This recalls the words of the Griot on page 29 of D. T. Niane’s Sundiata: Epic of Old Mali (1965); as translated by G. D. Pickett that “Men’s wisdom is contained in proverbs and when children wield proverbs it is a sign that they have profited from adult company”. The young Dora profited from adult company in a way that shaped her choices throughout life.

Chapter 2, entitled “A child who is carried on the back will not know how far the journey is” recounts how Dora’s parents decided to send the nine-year-old girl to the village to hone her domestic skills. Her parents might have appeared cruel but that experience was to define and shape her interconnectedness with her people later in life. Entitled “What an elder sees sitting at the base of a tree, a child must climb the tree to see” the third chapter celebrates the respect her father (fondly called PY – Paul Young Edemobi) commanded due to his generosity and consideration for his people.

In chapter 4, Dora arrives in the village and becomes immersed in village life, such as fetching water from the stream, fetching firewood, farming and so on. It does not take her long to adapt and adjust to life in the village and to realize that “It takes an entire village to raise a child”- the title of the chapter.

The fifth chapter is entitled “If you are building a house and a nail breaks, do you stop the building or do you change the nail?” It recounts her experiences (curricular and non-curricular) in school, including a critical lesson on punctuality. It also shares some experiences on the home front, such as when she almost fell to her death from an eroded cliff, and being afflicted by pneumonia which almost took her life.

“No matter how full the river, it still wants to grow” is the title of chapter 6. It provides a profile of Dora’s maternal grandmother, Nne, who is a no-nonsense, kindly woman shaped by the best values of her culture in harmony with Christianity. It is inevitable that contradictions will arise from holding on to dual systems of belief and practice. Thus, Nne actively participates in making Dora undergo female circumcision – more bluntly termed female genital mutilation.

In chapter 7 “What else is expected of a cigarette if not smoke” we read the account of Dora’s completion of primary education, her admission into Queen of the Rosary Secondary School (QRSS), Nsukka for her secondary education, life in the boarding house, and the sudden disruption of her schooling by the Nigerian civil war. She is forced to return to Isuofia and re-unite with Nne, her grandmother, all the while wondering whether she would ever see her nuclear family.

Chapter 8 is entitled “A boat cannot go forward if each rows their own way”. It is full of a child’s recollection of the cause(s) of the civil war as analysed by adults, some of whom we could safely say did so without full knowledge of the facts. The persona is only consoled by re-uniting with her family “And so it came about that my entire family, later joined by Papa journeyed east along with thousands of other families on overcrowded trains that smelled of death, of fear, and of decay.” (p.54).

It is often said that adversity and prosperity reveal the true character of a person. Self- professed values suddenly disappear, replaced by cruelty and rarely kindness. This is manifest in chapter 9 with the title “Don’t think there are no crocodiles just because the water is calm”. When Dora arrives Nanka to re-unite with her nuclear family, she senses hostility from her uncle Benedict Obiekeli (Ben, Benu), who takes advantage of the situation to claim as beneficial owner the Edemobi’s properties which he had managed as caretaker or technically “Trustee”.

The experiences, devastations and effects of the civil war are covered in chapters 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15. Chapter 10 is entitled “A tree is known by its fruit” and recounts how Dora’s family became refugees, with her mother selling her wrappers so as to raise funds for family survival. In chapter 11, child (slave) labour under one Mr Nwokobia is censured with the pithy title “When the roots of a tree begin to decay, it spreads death to the branches”. One wonders if Dora Akunyili considers the civil war as one of the causes of the loss of the values which make us appreciate that “I am because we are”. Anyway, the consolation in this chapter is the fact that notwithstanding the war, life goes on as the marriage of Dora’s sister Gloria is a beautiful flower in the grim landscape of the thorns of war.

Chapter 12 entitled “An arrow can only be shot by pulling backwards” presents the loss of properties – real, money and other moveable items – which accompanies war. These reflections continue in chapter 13 with the title “An orphaned calf licks its own back’. Perhaps, the experience also makes Dora more prayerful. In her own words, “I spent a lot of time in prayer those days, as always calling on the Blessed Virgin to intercede on our behalf. I knew now more than ever that I needed the hand of God to fulfil his promise that ‘not only does He carry us in his hands, but He has engraved us on the palm of His hand’ (Isaiah 49:14-16). I had to trust that I was held in the palm of His hands.” (p.79).

The 14th chapter “One arrow can knock down an elephant” is the conclusion of the civil war experiences and effects. Dora’s father has lost his properties, her mother is diagnosed with diabetes, and her father dies at the age of 59 in April 1972, when she is only 19. While the cause of death is a subject upon which there is much speculation, Dora betrays her own thought “… that it was from a heart broken by the war”. (p.82).

“No matter the grief, nothing the eye can see will make it bleed” is the title of the 15th and last chapter of the first part of the book. It narrates the grand burial accorded Dora’s father and culminates in Dora assuming leadership of the family at the tender age of 19.

Part II, 1972-1994, is composed of chapters 16 to 28. This part covers her academic journeys, marriage, and involvement in community development. The first chapter of this part, chapter 16, opens with the thesis earlier established in chapter 1 with the following words “Even after Papa’s death, the Edemobi family name continued to earn me and the rest of the family the goodwill of others.” (p.91). Entitled “Those who are born on top of the anthill take a short time to grow”, it shows Dora’s adaptability under all circumstances – the good, the bad and the ugly. The family of Professor James Ezeilo provides the good and comforting which is crowned by Dora earning aggregate seven in the West African Examinations Council (WAEC) School Certificate Examination.

In chapter 17, Dora recognizes that “If you wish to move mountains tomorrow, you must start by lifting stones today”. That is the title of the chapter where, contrary to the expectations of most people, she decides to read pharmacy rather than medicine. The logic and passion of her argument, wins over her guardian Prof Ezeilo. The reader will also be struck by the ease with which she enters his office (office of the Vice Chancellor, VC of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka). I bet today the layers of bureaucratic security designed to shield the VC may be so multilayered that he can be killed before security information can get to him.

The riddle, “Who knows how water entered into the stalk of the pumpkin” is the title of chapter 18 which focuses on the shared interests and chemistry between Dora and Chike Akunyili, at their first meeting, each initially prejudiced by the purported arrogance of students of medicine and students of pharmacy. With the consent of their parents, they are married in chapter 19 entitled “A person who arrives at a feast when the cooked meat is being pulled out of the pot does not know what was endured by others to catch and cook it”. In chapter 20 Dora is pregnant and miscarries (“If a child hungers for a palm nut, it does not upset his stomach”) while her husband Dr. Chike Akunyili is compelled to go on the mandatory National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) programme in the village of Jaban Kogo in Kaduna State. Happily, Chike not only reassures her that miscarriage is normal, he makes impact at his primary assignment and is nicknamed Dr. Jaban Kogo.

In chapter 21, “A tree cannot stand without roots”, we are once more treated to the duality of human existence, sadness and joy, inflation and deflation. Dora has her first child, a daughter named Ijeoma and her second child, a son named Dozie, but is deflated by the diagnosis that her youngest sister Nwogo has diabetes. The pattern of sadness and joy continues in chapter 22 (“No matter how big a child is, she cannot deny that she was once carried on the back of a woman”) with the death of her mother and the birth of her third child, her daughter Somto (Somtochukwu – join me in praising God).

In the 23rd chapter entitled “Listen to the ground and hear the footsteps of the ants” we find that I Am Because We Are does not pretend to be a romantic biography. It is an honest and transparent story capturing personal and emotional pain as well as feelings of inadequacy and

failure. Dora enrols for a PhD. Her research suffers with the pressure of being a mother (indeed, nursing mother with the birth of Njideka, her fourth child, a daughter) and big sister to her siblings. The shocker is the disclosure that Dora’s husband, Dr. Chike Akunyili, the quintessential father and husband, is entangled in extramarital relations. Unfortunately, for her she “…confronted Chike, but I was unsure what I hoped to achieve with this. He didn’t deny any of it, nor did he fully acknowledge the truth. The diplomacy I had always admired in him was now working against the reality at hand… I wore the heartbreak like a second skin… a wound that never seemed to heal, whose scabs once pricked revealed the pus of a spreading infection.” (pp. 130-131).

Chapter 24 entitled “The ocean never swallows a person whose leg it does not come in contact” amplifies the tension between husband and wife, including the role of in-laws in exacerbating tensions. The emotional trauma worsens when in chapter 25, Dora’s youngest sister “Nwogo who had become my rock” (p.139) dies from being administered apparent fake insulin. The pain of this experience, which must have played a role in the passion with which Dora took on the NAFDAC job, is laid bare in the manner Nwogo is extolled. We are told that “…Nwogo’s potent charisma was in the pure satisfaction of being in her presence. Her generous heart added to the feeling that just being around her was a gift within which was the promise of joy.” (p.139). That the pain of her death is traceable to fake or adulterated insulin rankled more because she had been denied visa to America where the family had hoped better medical care and trustworthy medication would be available. Indeed, the title of the chapter is “A little rain each day will fill the rivers to overflowing.” It also exposes the duality of the persona’s world view – a Catholic who also recognises the power of the personal chi (spirit) (p. 140).

The title of chapter 26 is “Even as the archer loves the arrow that flies, so too he loves the bow that remains constant”. It exposes the childlike manner Dora embraces new and interesting experiences. It describes her sojourn in London following her acceptance to undertake a “doctorate with the Pharmacognosy Research Laboratories in the Department of Pharmacy” of King’s College, University of London. Her frugality and generosity is demonstrated in the manner she shares her allowance among herself, her children and her siblings; her reaction to the London underground and how she “… made friends with a butcher who let me have the unwanted parts of animals he slaughtered, including the head, hooves, intestines, and skin, which he gave me either for free or at a give away price. These I cooked and stewed into various delicacies such as isi ewu –…”. (pp.140-146). The joy of the London experience is the birth of her sixth child, a son named Obumneme (Is it by might?).

In chapter 27, Dora is back in Nigeria faced with the financial challenges of providing for her family and other deserving dependents. Entitled “Uwa bun doli – life is a hustle”, it is an account of her attempts at entrepreneurship, invariably defeated by human treachery, even in the ivory tower.

Notwithstanding the frustrations of her adventures in entrepreneurship Dora transfers her “duty of care” to the community. Thus, in chapter 28 “If the hen stops clucking, what will she use to train her children?” she secures stakeholder support, beginning with her fellow women and subsequently appealing to the men, to establish the Agulu hospital or health centre. Through

communal self-help eight months later Agulu has a hospital. Dr Dora Akunyili earns an appellation, “Ugogbe mmuta – which means ‘a mirror that reflects the virtue of good deeds to be learned and emulated’, or more simply put, ‘mirror of wisdom’…” (p.165). I only hope the government made it truly functional through the provision of equipment and personnel. We might go ahead to affirm that that was a “campaign” strategy by Dora to be considered for public office. For shortly after earning the appellation of “the mirror” she confesses that “I had a plan… I stopped over in Lagos at the home of a well-connected family friend … to talk to him about the possibility of a state government position”. (p. 165). Although her lobby for appointment as a commissioner does not succeed, she “… became a member of the Caretaker Committee of Aniocha’s local government” (sic) (p.167).

Part III, 1994-2008 is composed of chapters 29 to 45. It is about Dora’s stewardship as a public officer. It begins in chapter 29, “A good fruit cannot produce bad fruit, nor can a bad tree produce good fruit” with Dora’s appointment as a supervisor (designated Director) in charge of agriculture in Anaocha Local Government. Painfully, “It didn’t take me long to determine that my job description was on paper alone. Far from being expected to distribute the agricultural supplies, I was to become complicit in aiding an immoral practice of hoarding supplies for personal gain… The very caretakers of the well-being of the people were acting as the impediment to their productivity. It reminded me of the injustices of working for Mr. Nwokobia on his farm during the war.” (pp. 172-173).

A recurrent theme of The Story of Dora Akunyili is the negative alteration of human values in Nigeria which she attributes to the civil war. This is expressed on page 174 as follows:

“A country that was once governed to ensure law and order and respect for human life and dignity had turned into a world of mayhem, of every man for himself. Too many had died and much atrocity had been committed in the name of war and of survival. Our ndi Igbo community, which had once thrived in recognition of the least of its members, and by curbing the excess of egos, had reversed its course… The war effectively created a new reality, and Igbos went from self-sufficient communities that cared for the well-being of all to disparate people concerned only with survival, believing that the only way to live was to fend for one’s self and one’s family. The Igbo people knew not to count on anyone, least of all on Nigeria.”

She doesn’t despair in helplessness. She creatively defeats the system of exploitation to get the agricultural items to the rightful owners, hands on, by inviting them to the local government council office at Neni and personally disbursing their entitlements to them. Naturally, while she gains the acclaim of the beneficiaries, she also earns the enmity of the local government officials who were the beneficiaries of the old exploitative system.

“One who serves benefits by the service” is the title of chapter 30 which aptly narrates the positive consequence of her coup against the exploiters. Impressed by her handling of the distribution of agricultural inputs, the local government chairman volunteers to nominate her for higher appointment at the Petroleum Trust Fund (PTF). Interestingly, although the original plan was for Dora to serve as Anambra State representative, she is appointed Zonal Secretary of the

South Eastern region “…to co-ordinate all PTF projects that stretched across investments in roads and waterways, education, food supply, health, water supply, and a long list of other social projects.” (p. 180). Unfortunately for her, the PTF became a symbol of discrimination in Nigeria, in terms of budget allocation and promises unfulfilled. In her own words, “Those years working with PTF as the zonal secretary exposed me to the intricacies of a large bureaucratic arm of the federal government, the crippling lack of transparency, and the cost of individual shortcomings of staff…Above all, it taught me what not to do.” (p.182).

In chapter 31, “Tomorrow is pregnant; no one knows what it will give birth to” the despair over the fate of Nigeria (as gleaned through the public service) is punctuated by lessons to her children on the value of empathy. Indeed, she gives a practical demonstration with visits to her grandmother Nne in Isuofia. The chapter also contains the miraculous (and hilarious) account of how the Akunyili family won the United States Green Card Visa Lottery, with the consular official missing an evaluation document which recommended that they should be disqualified.

My personal creed that family is the greatest support structure is given credence in chapter 32 with the title, “A well-travelled child exceeds a grey-haired person in knowledge”. Firstly, her brother Anayo had become “… a business partner, a confidant, and my most trusted companion.” (p. 190). Secondly, she bonds afresh with her children collectively, which is also the subject of chapter 33, “If you pick up one end of the stick, you also pick up the other”. Watching the movie “The Titanic” with the children simply demonstrates that.

The catalyst for Dora becoming a remarkable public servant is captured in chapter 34, “He who tells the truth is never wrong.” It gives a simple account of her experiencing stomach pains; the misdiagnosis that she needed surgery; the trip to the United Kingdom for the surgery estimated to cost £17,000; the tests and treatment costing £5,000 only; leaving a balance of £12,000; her brave, honourable and unusual insistence that she should be given a receipt for the £5,000 only, and the balance of £12,000 paid back to the PTF. This event later served as her referee/recommendation for appointment to the office of Director-General of NAFDAC, where she earned national acclaim as a creative, hard-working, exceptional and incorruptible public officer.

Following the dismantling of the PTF, Dora returns to teaching at the university, earning the title of Professor in 2000. That is the subject of chapter 35 entitled “Every door has its own key”, a cryptic reference to the conversation between the then President Chief Olusegun Obasanjo, his aides, and some members of his cabinet, where the name Dora Akunyili is dropped as an honest Nigeria who returned money unutilized. Thus, in chapter 36 (“If the rain permits, the moon will shine”), President Olusegun Obasanjo personally calls her to a meeting where he offers her the position of Director-General of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) in 2001.

Chapters 37 to 47 are essentially on the NAFDAC years, the successes and the challenges. Thus, in chapter 37 (“The load is not too much for ants”), she embarks on re-engineering NAFDAC to match purpose and identity, through the conception of a vision statement that ripens into a slogan

“NAFDAC – safeguarding the health of the nation”. (p. 216). This is strengthened with critical internal stakeholder engagement – the staff of the agency.

Recognizing that “One should sip hot soup slowly” in chapter 38, engagement with the staff is taken to new levels of staff motivation. The office environment is made fit for the self- worth of the staff, their welfare entitlements are restored and expanded, including training as reward for good performance.

It is not all chest beating. In chapter 39 we are given frightening data on the menace of counterfeit, fake, adulterated and sub-standard drugs, foods, and drinks (including water) in Nigeria. This causes a need to redefine the task on the realization that “When the food is properly done, soft enough so that crumbs fall, it reaches the ant”. In redefining the task, Dora “… saw the way forward as having two branches: one, eradicate ignorance; two, eradicate fake drugs. These battles would have to happen in tandem, the success of one supporting the other. We had work to do.” (p.226).

Pursuant to the redefinition of the task, chapter 40 (“Sticks in a bundle are unbreakable”) is on the expansion of the scope of the stakeholder engagement firstly, to include consumers, the media, and the establishment of hotlines for the public to make reports. The NAFDAC registration number regime is revamped to allow for verifiability by the public. Secondly, high profile corporate stakeholders are engaged. They include banks, aviation, shipping, hospitals, doctors, pharmacies, patent medicine sellers, and so on. The law is fully engaged with law suits, including a high-profile case against Nestle, for importing expired milk.

The challenges of intimidation, including dropping fetish objects in her office, attempted armed attack, and offer of bribe are narrated in chapter 41, which is entitled “If you think you are too small to make a difference, you haven’t spent a night with a mosquito”. The high point of these attempts at intimidation and corruption is the assassination attempt on her (and her entire family) in December 2003. The account is in chapter 42 entitled “One who holds me to the ground holds himself”. It is cold comfort that the assailants are arrested; and they confess to who commissioned them. Although we are told that the mastermind was charged for attempted murder, no further account of the progress of the case is presented in the book.

Following the failed assassination attempt and increased security around Dora, the threats shift to her family, compelling her to relocate her son Obumneme to the United States. Furthermore, as recounted in chapter 43 (“There are no shortcuts to the top of the palm tree”) “The counterfeiters, frustrated by NAFDAC’s effectiveness and thwarted by increased security around me, continued to target NAFDAC facilities”. (p. 245). Dora also intensifies her prayers leading to the recurrence of 16 prayer points on page 248.

Notwithstanding the task at NAFDAC in chapter 44 (“We desire to bequeath two things to our children; the first one is roots, the other one is wings”) she undertakes another round of bonding with her family, by way of a Caribbean cruise. Her husband Chike is unable to join them.

In chapter 45, we learn that NAFDAC’s stakeholder engagement enters the realm of international diplomacy. Indeed, as the title says, “When the elephant places his foot on the ground, one sees his footprint”. This is done through forging “strategic relationships with international

organizations such as WHO and UNICEF in order to garner international support, especially given the complex and interconnected nature of trade.” (p.253). This is followed by the drastic closure of markets in Aba, Kano and Onitsha “… in order to carry out a full-fledged mop-up …” with the “full support of the federal, state and local governments.” (p. 254). The statistical record is impressive – destruction of fake, counterfeit, expired, banned and smuggled drugs worth $53 million, 45 convictions secured against counterfeiters, and a drop in the percentage of unregistered and unregulated medicines in circulation from 70 percent to as low as 20 percent by 2008. Not surprisingly, other countries like Uganda and South Sudan elect to learn from NAFDAC while Dora receives honours and awards from universities and international organizations.

The curtain at end of Part III of I Am Because We Are is drawn with 19 photographs spread across four sheets or eight pages. Again, the reader is struck by the modest, austere number of photographs. The impression you have is that the pictures are not for self-glorification but merely to provide evidence that the book is about a real person, much like the captcha to prove that the person installing an application in the computer is not a robot. Nevertheless, the photographs cover the essential Dora – family, academic, public service as exemplified by the NAFDAC years, and awards.

Part IV is host to chapters 46 to 53. It covers her departure from NAFDAC, her appointment as a federal minister, and the failed attempt to be elected a senator. Thus, in chapter 46 (“The forest that denies you firewood has massaged your neck”) the new president, Umaru Yar’Adua invites Dora to serve as a minister. She dreams of heading the Ministry of Health as “The health ministry portfolio would be a natural evolution of my work at NAFDAC…” (p. 259). Alas, she is assigned to the Ministry of Information and Communication, to her disappointment. However, she is consoled because “All signs pointed to Yar’Adua wanting to leverage the trust I had built up in the hearts and minds of the people to deliver his messages” (p. 261).

Curiously, chapter 47 is entitled, “I am because we are”. Here, she reports for duty at the Ministry of Information and Communication and recalls the family values learned from her father’s stories in order to address Nigeria’s image. Thus, is born the rebranding campaign with the slogan “Nigeria – Good People, Great Nation” through a competition for Nigerians (p. 266). We are told the challenges of the campaign, especially the contradiction between aspiration and the reality; the fact that Nigerians don’t see themselves as change agents, regrettably pointing at others instead. This reservation, even among neutrals, is captured in an article in the Economist of April 30, 2009 with the title, “Good People, Impossible Mission”, amplified by another opinion that “But it’s our leaders that are our main problem, not the people”. (p. 269).

Chapter 48 (“A lie has many variations; the truth has none”) is an insider’s account of the turmoil caused by the illness of President Yar’Adua, his failure to properly transmit power to the vice president, and the frustration of lack of credible and reliable update on his situation. As information minister, she resolves to stop answering questions or putting out statements on the president. However, instead of throwing up her hands in helpless despair, Dora takes action by writing and circulating a memorandum to the federal executive council, demanding that the

president should transmit power to the vice president in writing, or that, by resolution, the vice president be named acting president.

If Dora thought her courage would embolden others, she was mistaken. As we read in chapter 49 (“Where the corpse lies is where the vultures congregate”) she is compelled to withdraw the memorandum to present it at a future date. Fortunately, on February 9, 2010, the National Assembly succumbs to public pressure and empowers the vice president to act as president, pending the return of the president. Two weeks later on February 24 the president is flown back home. He eventually dies on May 5, 2010 and Dr Goodluck Jonathan is sworn in as the substantive president.

Dora provides an insight into the working of the government of President Jonathan, a dysfunctionality created by the president’s personal qualities. Thus, in chapter 50 entitled “Fire makes strong salt” she informs us that “I was not the only square peg in a round hole. The announcement of his cabinet of mismatched candidates and portfolios was one of the first signs of the woes that would cripple Goodluck Jonathan’s government. The very talent for which he was chosen to be vice president to Yar’Adua was marring his presidency. Nigeria needed a decisive leader who was willing to rock the boat as needed. Instead, we got a quiet, slow-moving man with a distaste for speed and a preference for neutrality to the point of inaction”. (p. 282). Given the character of Dora, it is not surprising that she elects to resign in order “…to have more authorship on the direction of my journey, free from the whims of a seated president” (p. 282). In order to serve her people, she decides to contest for the Anambra Central senatorial district on the platform of the All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA).

The campaign trail reminds her that “When you wrestle with a pig, you both get dirty, but the pig enjoys it”. That is the title of chapter 51. She is shocked that Dr Chris Ngige who had blessed her bid for the seat, joins the race too – against her! Chapter 52 recounts the intrigues in the electoral process, especially the cavalier attitude of her opponents, leading to her loss by a narrow margin of 489 votes. It is a realization of the truth in the wellerism that forms the title of the chapter: “The millipede says that one who steps on it cries out, but it itself who was stepped on does not cry out”

Dora contests the loss of the election in court and still loses, making her to assert in chapter 53 that “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”. She devotes herself to introspection, devotion to God, and reconnection with her children.

Part V, 2012 – 2014 has chapters 54 to 60. In chapter 54 (“A good thing for a house to lack is sickness”), Dora is diagnosed with cancer, after surgery for fibroid. She undergoes chemotherapy treatment. She tries to stay positive, yet another form of painful realization hits her

– she did not teach her children how to cook. The chemotherapy treatment continues in chapter 55 entitled “Two events are in the sky: if rain does not fall, the sun will shine”. Dora tries to spend more time with her children, conceding that she was wrong to try to dictate a career path to Chidiogo (ChiChi). It is ironic that the same ChiChi puts her writing skills to the writing of this book I Am Because We Are.

Chapter 56 entitled “The axe forgets, the tree remembers” proclaims the bleak news that she has a rare, highly malignant cancer of the uterus. Impervious to treatment; it simply squeezes the life out of her. It makes her cranky, irritable and cankerous but she does not lose faith in God. We learn in chapter 57 that the illness is worsening, consistent with the title of the chapter that “No matter how the rain beats the guinea fowl, its colour remains the same”. Dora stays busy as much as her strength would allow by attending the national conference and speaking while standing, even falsely claiming that she is in good health.

Maintaining faith and trusting God for healing, in chapter 58, she undertakes a pilgrimage to Lourdes in France, in the belief that “A fully grown-up tree cannot be bent into a walking stick”. She is not healed; so, she returns to Nigeria to continue with medical care at a Turkish hospital in Abuja. That is the subject of chapter 59 (“The young bird does not crow until it hears the old ones”), where her faith and hope combine to accept the referral that a hospital in India had developed a revolutionary treatment for cancer. The revolutionary treatment promised turns out to be the same old chemotherapy applied in an inhospitable environment and manner. And since “Ukwa ruo oge ya o daa – the breadfruit will fall when it is ready” in chapter 60 “on June 7, 2014, my body gave up to join me. I was fifty-nine.” (p. 337).

Part VI is entitled “Chidiogo – My Mother and I” 2014-2021. It has only three chapters, 61, 62, and 63. The narrator is now clearly Chidiogo, reflecting on her relationship with her mother, the now late Dorothy Nkemdilim Akunyili, finding virtues and flaws in her character in equal measure.

Chapter 61 which is entitled “No one shows a child the sky” recounts how the writer Chidiogo Akunyili-Parr received news of her mother’s death and how the initial pain is blunted by her conversation with a stranger on a ferry.

Chapter 62 (‘If you want to know the end, look at the beginning”) describes how news of the death of Dora Akunyili was made public. It is followed by Chidiogo’s reflections on her relationship with her mother, how circumstances kept them apart making her feel “…abandoned and unseen. Unloved and unwanted – of not being chosen. In those moments I have to remind myself of all the ways I am held by a greater force, which now includes the very spirit and essence of my mother. It brings me a smile to know that our bond could be formed after her death… For a long time, I regretted the many years apart.” (p. 355). In spite of these words, Chidiogo experiences epiphany, namely that closeness is not always forged in physical proximity.

Similarly, “Peace is costly, but it is worth the expense” is the title of chapter 63, the last chapter of I Am Because We Are: The Story of Dora Akunyili. It is a continuation of Chidiogo’s reflections and the lessons from her relationship with her mother and life in general. For instance, “I saw then, as I do now, the fallacy of living one’s life for another” (p.362). Furthermore, Dora’s character of contrasts is exposed on page 362 where Chidiogo reflects that, “The way I saw things, everything could have been avoided if we had a relationship that allowed for us to talk before resorting to attacks…She was quick to anger, but just as quick to cool her temper. She could be spitting fire one minute and smiling the next, like when the gas is on a moment too long and the fire catches in a burst of flame, only to settle a few seconds later.” (p.362).

The rest of the chapter describes the funeral obsequies for Dora, dovetailing into the voice of intuition to write the book “Write in my voice… Speak with all voices” (p.366) underscoring the theme of healing.

The Epilogue and Afterword, which are further reflections follow. It is interesting that the epilogue is entitled “Chidiogo and Dora” and subtitled “The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second best time is now.” It reflects on the title of the book, its relationship with the concept of Ubuntu, in justifying that “… my story can be one of your guides”. (p. 372).

The Afterword is subtitled “A bird on an iroko cannot be shot down with a bow and arrow”. It represents another chapter in the tragic experiences of the Akunyili family: the accidental but fatal shooting of Dora’s husband, Dr. Chike Akunyili. Chidiogo proposes that “If I am because we are then my father’s pain, gasping for breath in his last moments, is because we as a nation are in pain… The current path, marked by injustices, atrocities, exploitation, and frustrations, only leads to more senseless death and pain. We can choose a different path.” (p.377).

CLOSING WORDS

I Am Because We Are: The Story of Dora Akunyili is a biography which, using the life of the heroine, mirrors the tragedy of Nigeria. Joy and hope are short-lived, continually accompanied by the shadow of evil and sadness. Given the work Dora Akunyili did at NAFDAC and her rebranding campaign as information minister, can we honestly say we have made progress as a nation? It is anchored on a philosophical framework of healing for the nation, but the fact that Dora’s cancer does not succumb to healing is a grim reminder of the shadow of decay in values accompanying us in every area of national life. Since a book is not judged by its social and historical import alone, let us return to the issue of form and style.

The book is written in free-flowing prose packaged in rich imagery. For instance, page 78 opens thus:

“Nsukka, the home I had known for those brief months of peace as a secondary school student, was now a shell of itself. The once bustling university city had been heavily bombed by Nigerian soldiers during the war and had taken on the dull colour of defeat and death. Street lights hung gutted, their inner tendrils a disturbing echo of human bodies laid open against the once pristine pavement. Neighbours greeted each other in the light of day, trading stories of misfortunes, mentally tallying the number of friends lost, as information travelled back along with people.”

The above passage is a weight on the mind. In contrast on page 146 the author’s sense of humour lifts our spirit where she refers to “…bushy-tailed rats that ran freely around the city – squirrels, they were called.”

These metaphorical sights and sounds permeate the whole work and provide opportunity for the author to simultaneously engage in social commentary, on moral values, and the effects of war.

Furthermore, this fluidity in the narrative moves the story like a vehicle with an eight- cylinder engine gliding on a smooth highway without fear of potholes. It describes the dramatis personae in all their virtuous or villainous aspects.

Consequently, and thankfully, dialogue among the characters merely advances the story without clogging it like excessive and complex punctuation. Interestingly, in conversation, members of Dora’s family often switch codes between English and Igbo, as if to remind the reader that English, a medium of international diplomacy, may have been chosen to tell the story, but the characters are still Igbo. This literary device of code-switching might have confounded and wearied the non-Igbo speaker, but for the fact that there is an instant translation, similar to the syntactic structure of placing qualifiers and modifiers close to the words, phrases and clauses that they modify. For instance, on page 52, we read “Alu emego anyi”- an abomination has fallen upon us – was a lamentation on many tongues.” And on pages 185 to 186 we read “They joined me in spontaneous dance punctuated by shouts of joy. Cries of ‘God is good, ‘Chineke Igwe’ and ‘Chi mooo’ filled the physical space as much as our emotional one”. Lastly, on page 326 Dora informs us that “Every night, before we went to sleep, I asked my daughter to pray with me: ka Mummy bia mee m operation nábani – that mother Mary would come and operate on me at night.”

The use of proverbs and pithy sayings as the titles of the chapters foreshadow the contents of the chapters. They are like the topic sentences of paragraphs in essay writing. From a literary point of view, it also reminds the reader of Chinua Achebe’s writing.

The work is not perfect. Firstly, there is no table of contents to help the reader make specific searches. Secondly, on page 17, the author claims that there are 768 local government areas in Nigeria. It would appear that this number neglects the six area councils of the Federal Capital Territory. The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended) actually recognizes 774 local government areas, inclusive of the area councils of the FCT.

Outside of these, there are no proof errors or other defects with significant impact on the enjoyment of the book, its flow or its facts.

The Story of Dora Akunyili invites you to know and appreciate how an extraordinary public officer was forged – by her parents, especially at the feet of her father, her grandmother, her uncle making her to conclude that “It takes an entire village to raise a child” (p. 20). The account is transparently candid without being bawdy, exposing intimate family details as well as character virtues and flaws in our heroine. However, the choice to remain steadfast on the path of moral rectitude, even in the face of temptation, threat or intimidation belongs to the individual. It is gratifying when close family like one’s spouse can say “Dora, … you can change the world from anywhere” and follows it with the rhetorical question “… but since when has anyone made you do what you don’t want to do?” (p.262). She answers the question, without vocalizing it thus: “I was ultimately responsible for my actions, and I had no intention of being compromised”. (p. 263).

Let me now invite and allow you to personally read and enjoy, as I did, the pleasures of I Am Because We Are: The Story of Dora Akunyili.

Thank you.